Dear Mario,

I wanted to get in touch just now to wish you a happy birthday on your one hundredth anniversary. Your special day is 1st August and although you won’t be joining the celebrations in person I assure you that the things you did in the seventy five years you spent with us out of that one hundred will be remembered.

I’ve been in Senegallia recently and I’m sure you’ll be delighted to know that there are still a lot of people who love to tell Mario Giacomelli stories and all of them are told with love.

Here I am in the U.K., in Gloucestershire, and I’m thinking about, and remembering, the landscapes of the Marche region of Italy.

I’ve visited your home town of Senegallia a couple of times and there are some photographs here of places you would have known. I send them to your memory as a birthday gift.

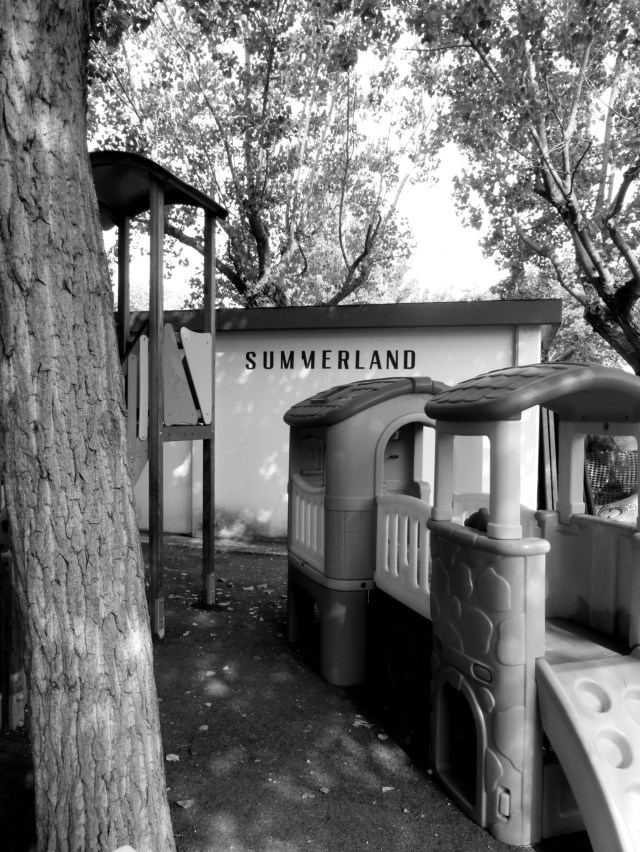

I am now, as I was when I first heard of it, amazed that you once owned a campsite called Summerland. But I suppose it’s just an ordinary thing for an ordinary man, born into poverty but doing alright for himself, to buy into in the hope of a bit of profit.

I have a strong impression that you were not someone for whom wealth, which you no doubt enjoyed in the latter part of your life, would ease the way into easy living.

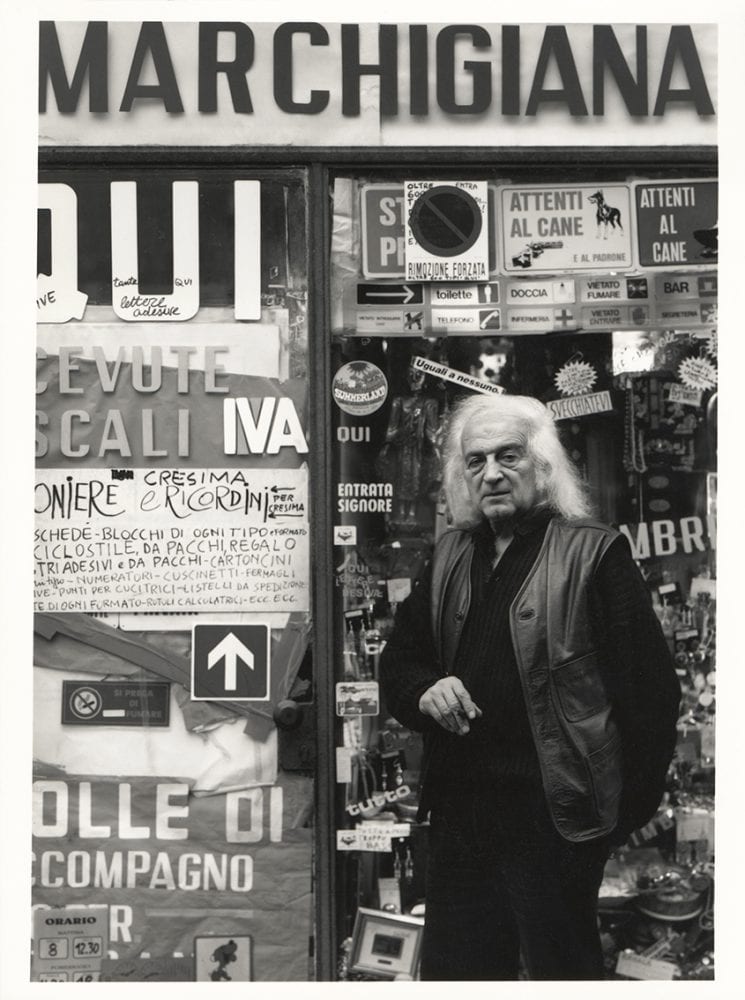

You kept the Tipografica Marchigiana, your commercial printing shop, open for most of your life.

The first time I visited the site of that business it had changed into a very stylish clothes shop and the young man who ran it had two original prints of your photographs on the wall.

He took me into the basement where your darkroom had been.

I’ve seen pictures of that darkroom and smiled at the chaos you worked in. The tattered photographs and portraits of people you admired, the newspaper cuttings taped to the walls and the notes to yourself along with sketches for future projects were like glimpses into your mind.

When I saw the room it was small and empty with bland, painted over brickwork.

The shop you spent most of your life in is now empty and locked up and, just to get all the bad news out at once, your beautiful 1970s house, full of glass and light, has been pulled down and replaced with holiday flats.

A young woman at your campsite, who told me that her boyfriend’s grandfather used to go out painting with you, said that nothing is sacred in Senegallia now and everything bends the knee to profit.

Thankfully, you don’t have to worry about all that any more.

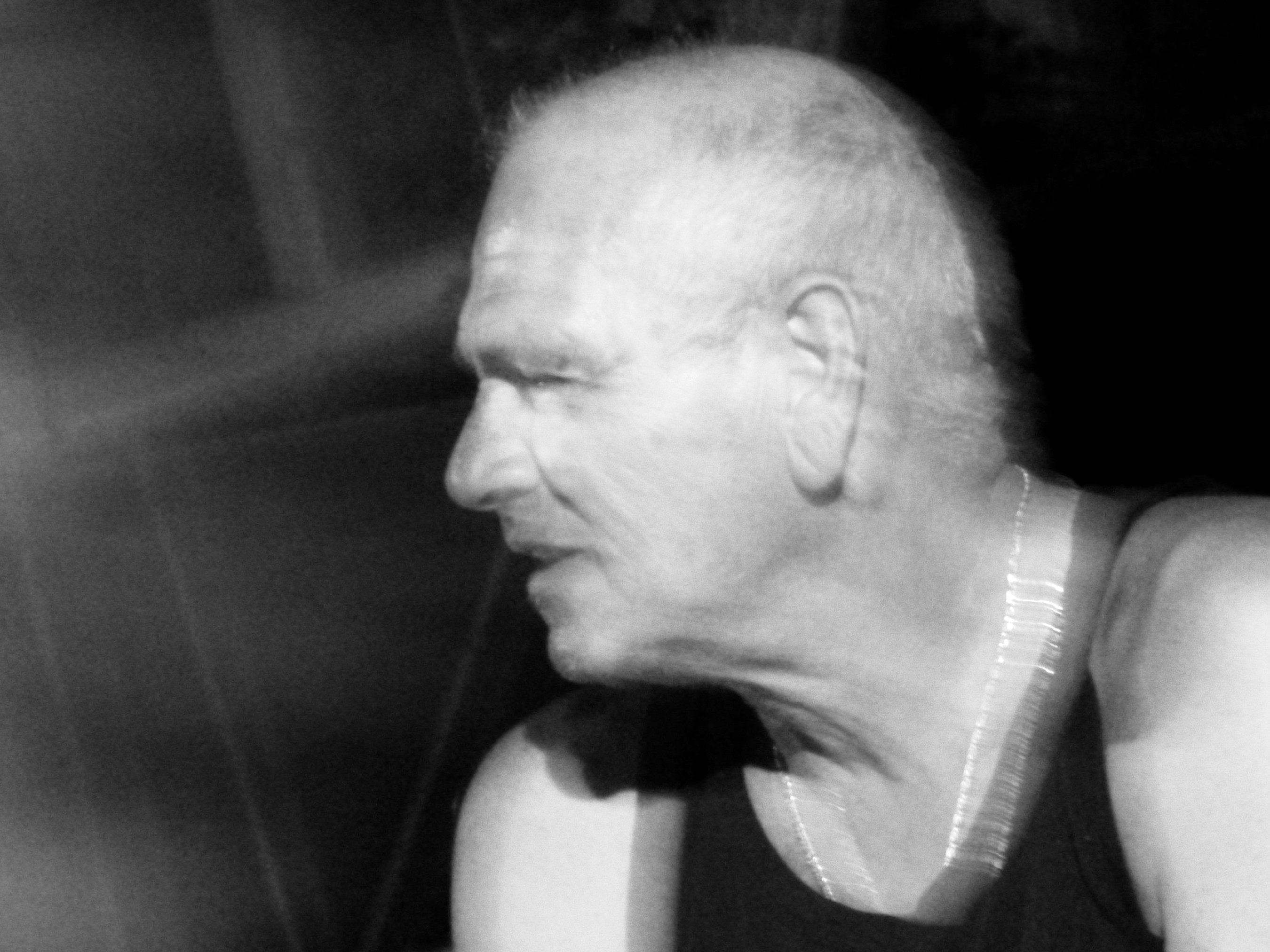

There are pictures from the time that you operated the Tipografica which show the windows covered with signs offering services and products. They show you too, leaning against the doorframe with the small cigar you never seem to be without and, most often, with a group of people. Always talking and often laughing.

I understand that you worked all week in your shop and made photographs at the weekend.

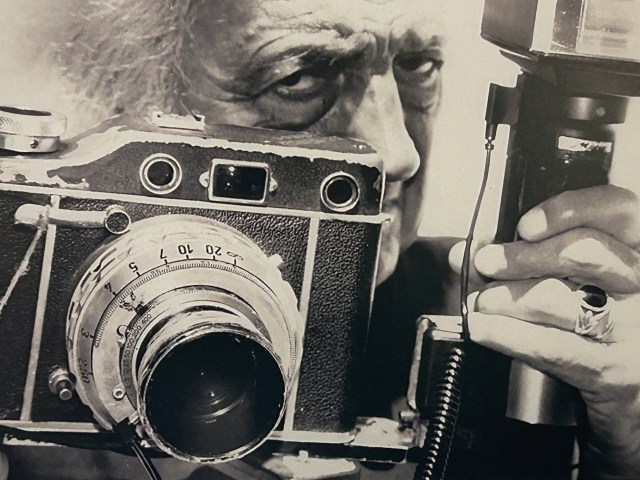

You took a cumbersome, second hand, Kobel rangefinder camera with 6×9 plates and made photographs with double exposures, deliberate blurred movement and soft focuses in the landscapes and with the people within a few miles of your home.

These days all of those camera techniques are on show wherever you see photographs. The internet is full of them. Harsh contrast black and white prints are everywhere, including, I have to confess, in the collection of photographs I’ve made over the years. I, too, have been influenced by what you did.

I hope I’ve wandered into your style out of respect and followed your lead as an homage rather than simple copy cat image making.

But it’s not just the images I find fascinating although they must have been like disruptive dreams when they were first seen by the group you were part of.

After the war you were an active member of Group Misa, named for the river that runs through Senigallia and founded by the photographer Giuseppe Cavalli.

Post war Italian photography like yours was speeding away from an aesthetic favoured by the Fascist government and found its significant new influences in the cinema and the work of directors like De Sica and Rossellini.

You managed to travel a few steps further than the rest of your group and developed a style which imbued documentary realism with abstraction.

The landscapes which resemble giant fingernail scrapings across fields, your priests at play in the snow and the isolated villagers and farmers eyeing us through their uncomfortable relationship with your lens, have become icons.

So, too, have the pictures which live as one with the grit of the torn landscapes but which were made with old people at the end of their lives who showed us the lines and creases of their ruined bodies. You spoke of these pictures as being cruel but they are also among the most honest photographs ever made.

Now, here’s the thing I mean when I tell you it’s not just the images, staggering though I think they are, which are the remarkable thing contained in your work.

That series of images of frail old people contains all the threads which I think makes your work so compelling.

Firstly, they were made in a home for the elderly in Senegallia where your mother worked as a laundress.

This simple fact locates the work within the boundaries of what was familiar, local and had meaning beyond the subject. You managed to embed layers of story into the collection of photographs.

I’ve visited the building which housed the home and it was local to the place you grew up in. This and your mother’s involvement meant that it must have been in your mind from a very early time. It was part of where you came from and, of course, it represented where we are all going.

You exhibited these photographs in about 1954 under the title, ‘Hospice’, and continued working on the series until 1983.

That represents a long time for a photographer to be working on a project and that is the second remarkable thing about your work.

It evolves over time. It grows with you and changes as you change but always stays consistent to its own, and your own, personality.

In the mid 1960s you changed the name of the series, renaming it ‘Death Will Come And It Will Have Your Eyes’, after the first couple of lines of a poem by Cesare Pavese, ‘Death will come and it will have your eyes – this death that accompanies us from morning till evening, unsleeping.’

This connection between poetry and photography is the third ever present element in your work.

Your famous young priests at play in the snow was titled, ‘I have no hands that caress my face’, from a poem by Father David Maria Turoldo about young men who seek a solitary religious life.

The collection, ‘Spoon River’, which pursued the technique of double exposures and composite images, was titled to reflect the influence of the poem ‘Caroline Branson’ from the ‘Spoon River Anthology’ by Edgar Lee Masters.

The techniques here are the fourth of the constant presences in your photographs.

In the ‘Death Will Come …’ series you used a flash very near to your subjects, discovered unusual and disturbing points of vision and, as the series progressed, you began to print onto paper that was curled and bent rather than flat under the enlarger.

In your landscapes you removed horizons and with them our ability to read the pictures in an easy way.

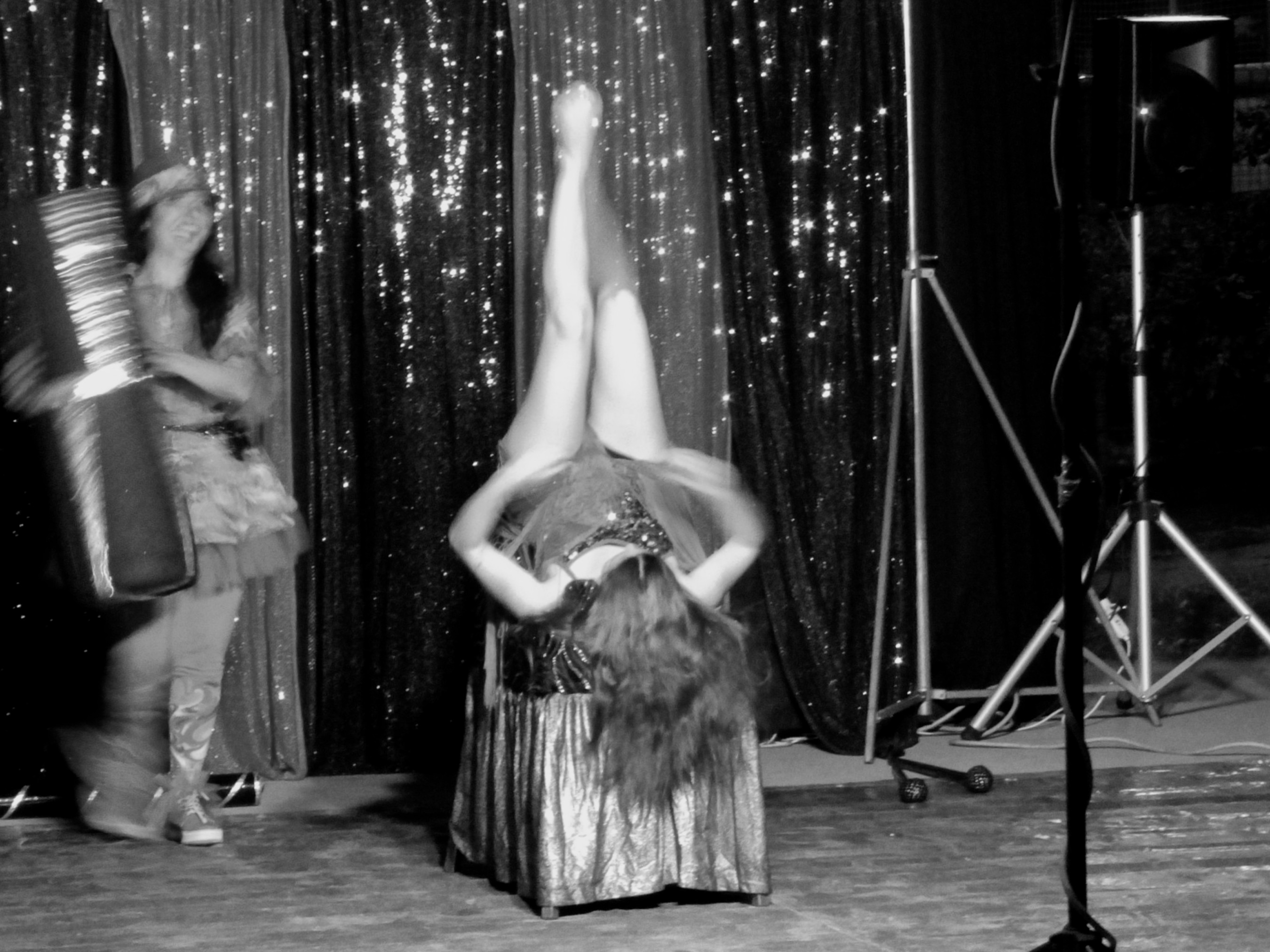

‘Spoon River’ and your late work let rip with double and treble exposures, your own portrait with masks and other props lurking in the background, wires bent like strange hieroglyphs twisting between desolate over exposed buildings and the sea playing an elemental role with figures often superimposed over the waves.

None of your photographs were without movement and the tasks you imposed on them are also fluid and this is the final element of what I find wonderful about your work.

As time went by and your restless relationship with your pictures progressed, images from one series would begin to turn up in another.

As you got older your photographic poems got more complex, more abstract and more personal.

They became clearly autobiographical with titles like ‘My Marche’, ‘The Sea Of My Stories’, and, late in your life, the strange and mysterious, ‘I Would Like To Tell This Memory.’

You died in 2000 after a long illness.

In 1987 there was a comment of yours recorded which runs, ‘Of course photography cannot create nor express. But it can be a witness to our passage on earth, like a notebook.’

It’s been nice to chat to you, Mario, and to know, from you, that it’s rewarding and interesting to find ways of thinking of photographs which makes them important and a way to a stumbling understanding of the world.

I know that you are aware that you have been extremely influential in my own photographs and I apologise if, occasionally, I’ve drifted close enough to at least one of your signature styles to rule out of court any notion of originality on my part.

By and large, this collection, which I’m sending to you as a birthday present, owe more to your observation than your technique.

If photographs can be witness to our passage on the earth then these are a notebook recorded on my passages through Senegallia.