I have memories of Vence, which sits in the Alpes Maritimes between Nice and Antibes, which are based on a proper tangle of truth and fiction. To me it’s a strange place where complicated theatres have been played out and the stories told have been interpreted and reinterpreted over and over again whilst the unfolding of actual events gets muddier.

That’s no doubt because the stories are mostly about artists and their complicated lives.

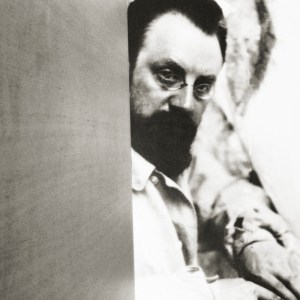

The town is not far from the village of St. Paul de Vence where the painter Marc Chagall lived and died. Some of his most beautiful works were made there and there he is buried.

There are reasons aplenty to celebrate Chagall and his time in St. Paul where he had the opportunity to be reasonably quiet. A lot of his work was made in the melting pot of some of the most turbulent moments of the 20th Century.

I love Chagall’s work for its compassion and insight but I have stood by his grave and recalled what are reported to be events which were played out on that stage. If his work gives us a glimpse into the human condition then so too does his funeral, but in a somewhat different way.

The cast of characters was interesting. I understand that Pablo Picasso’s widow, Jacqueline, embraced Chagall’s widow, Valentina, perhaps whispering in her ear something about what it means to be the surviving wife of a rich and famous painter. Chagall’s first wife, Bella, had died in New York in 1944 after being his muse and the beautiful mysterious woman in so many of his paintings. Their daughter, Ida, was there.

Someone in the crowd wanted to say the Kaddish and Ida refused to hear it. But as the coffin was lowered into the ground an unknown young man, possibly a Yiddish journalist, stepped forward and quietly uttered the Jewish prayer for the dead.

Chagall had one son, David McNeil, whose mother was neither Bella nor Valentina. He was there too but the family refused to have him sit with them and he stood alone, crying in a corner.

Vence and the area around it bristles with the leavings of great artists.

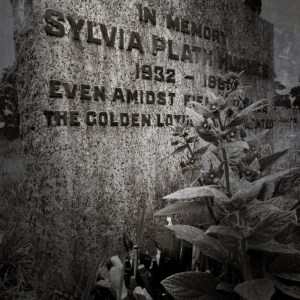

Matisse was famously involved with the creation of a chapel in Vence and I became aware of a story which placed an event, involving Sylvia Plath, on the terrace of that chapel.

The building of the chapel was an act of love on Matisse’s part. For Sylvia Plath, it represented the crossroads of passions which eventually lead to her relationship with Ted Huges and whatever pain that involved.

In 1941 Matisse was diagnosed with abdominal cancer. The complications arising from his surgery almost killed him and left him much weakened. He placed an advertisement for assistance. As a result, he was helped through his long and no doubt painful recovery by a young part time nurse called Monique Bourgeois. A deep Platonic friendship developed between them which was strong enough to persuade Matisse to ignore his innate Atheism to become involved in the making of a Chapel.

In 1943 Monique Bourgeois entered the Dominican Convent in Vence and became Sister Jacques-Marie. She told Matisse of plans the Dominicans had to build a chapel beside a girl’s high school a short distance along the avenue from Villa le Reve. She asked him to help with the design.

His collaboration with the Dominicans was born out of profound gratitude, friendship and love.

The Chapel of the Rosary is an oasis of light and calm.

At its side is a terrace filled with the scent of flowers and surrounded by trees.

The terrace was visited by Sylvia Plath in the early days of 1956.

In her final months as a Fulbright fellow at Cambridge, Sylvia Plath was ending a love affair with Gordon Lameyer, sleeping with Richard Sassoon and balancing a blazing sexual relationship with Peter Davidson.

She spent Christmas in Paris with Sassoon who turned his back on her after a monumental row on the terrace of the Matisse Chapel.

Emotionally exhausted and scarred, she returned to England where she was taken to a party at the Women’s Union in Falcon Court Cambridge. Her date on that evening was Hamish Stewart but here she met Ted Hughes for the first time.

Hughes was with another Cambridge student called Shirley whom he had asked to live with him in Spain where they would both disappear leaving everything they knew behind.

It seems that Hamish Stewart punched Hughes at the close of the party. Plath and Hughes had been enthusiastic about each other. They had danced, stamping their feet on the kitchen floor. Hughes ripped a red hair band from Plath’s head and pulled out her earrings. After a passionate kiss, watched by Shirley, Plath sank her teeth into Hughes’s cheek drawing blood and leaving a scar which took months to heal.

It would seem that on that quiet and gentle terrace, Sylvia Plath, through the violence of rejection, was propelled onto the first steps of a journey through which passion and destructiveness played equal parts and which ended so tragically.

It’s not a bad place to spend a little time to reflect on the fact that love has many faces and the experiences born from our different interpretations of what that means are very different indeed.

,